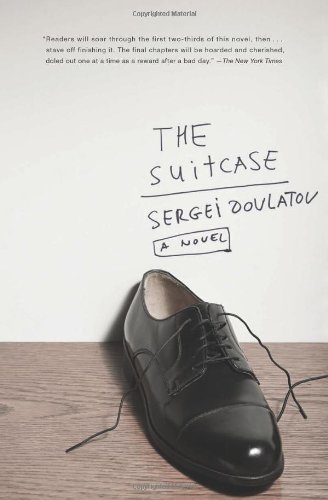

The Suitcase by Sergei Dovlatov

Counterpoint Press, 136 pages. The government of the Soviet Union (1922 - 1991) produced an army of disasters in their day, but no one can ever fault them for giving us Sergei Dovlatov. Born just after the Nazis invaded Mother Russia, Dovltaov would survive the war and go on to be a soldier, prison guard and journalist before escaping to the United States. Anticipating "creative non-fiction" years before the term was ever invented, Dovlatov wrote in a terse, comical style in the voice of a narrator created in his own image. The Suitcase is no exception. A wry collection of short stories about a Russian named Sergei - who was once a prison guard, worked as a journalist and emigrated to the States - The Suitcase merrily blurs the genres to create a work that is entirely unique.

The premise for the collection is simple enough to be envied: upon leaving Russia, Sergei (the character) is allowed to take only a single suitcase. He fills it with 8 seemingly innocuous possessions and then proceeds to tell us why. Each possession, of course, is intimately linked to a certain part of Sergei's life in the Soviet Union, circa 1965. Like the four parts of Shakespeare's Henriad, each part can be seen alone, but to do so would only deny their glory. Equal parts satire, farce and political commentary, the interconnected tales shine a bright light on the comical absurdity of Soviet life. In The Finnish Crepe Socks, young Sergei gets involved with a smuggler, who knows he can make a fortune merely by selling the eponymous clothing on the black market; later, in A Decent Double-Breasted Suit, Sergei tries to con his newspaper into paying for some new clothes and soon gets his wish, with a little help from the KGB.

We might never know exactly how much of these stories are actually true. In A Poplin Shirt, Dovlatov gives one account on how he met his wife. But in The Colonel Says I Love You, found in another Dovlatov collection, he gives a much different story. Dovlatov appears to have rewritten his life about as often as he wrote of it, making it a Herculean task to separate fact from fiction. But I suspect that is the point. Dovlatov was, after all, writing about Soviet Russia, a world where the propaganda machine ensured that fact and fiction were blurred all the time. Like much of Dovlatov's work, The Suitcase is the literary representation of Soviet Russia itself: Kafkaesque tension walks hand in hand with an almost Wodehouse-ian style of farce.

Equally engaging is Dovlatov's bare bones style, which at times makes Hemingway look verbose. His tone is almost conversational, as if you have just sat down with him in a bar. "This happened eighteen years ago," he might say, or "This is the story of the prince and the pauper." His narrative slips into digressions, allowing Dovlatov to make more than a few wry observations. "I'm convinced that almost all spies behave incorrectly" he writes in A Decent Double-Breasted Suit, before going on to explain how spies should behave. Later, in An Officer's Belt, he observes that "the worst thing for a drunkard is to wake up in a hosptial bed. Before you're fully awake, you mutter 'That's it! I'm through! For ever! Not another drop ever again!".

But perhaps the best representation of Dovlatov comes from this short paragraph in The Winter Hat:

"I took a swing, remembering the lessons of Sharafutdinov, the

heavyweight champ. I took a swing and fell on my back.

I don't remember what happened. Either it was slippery or my centre of

gravity was too high...In any case, I fell. I saw the sky, enormous, pale

and mysterious. So far away from my problems and disappointments.

So pure." (pp102.)

There it is: brief and comical, yet intimately revealing of his own character. It's also indicative of his tendency to make casual references to all sorts of Russian artists, celebrities and politicians, many of whom have slipped into obscurity (at least in the West). Thankfully, there's a helpful glossary supplied by either the editors or translator Antonina W. Bouis. Ms. Bouis deserves a special mention for succeeding in translating Dovlatov's voice into English, which couldn't have been easy - I don't know what the Russian equivilent of words like "refuseniks" or "Caucasian patriotism" might be, but it gives a sense of Dovlatov's playfulness when it comes to language.

With more of Dovlatov's work being re-issued, one can only hope this is the start of a revival in his work. It may be hyperbolic to say he could give Chekhov a run for his money, but as a short story writer, Dovlatov is exemplary and definitely deserves to be better known. Memo to teachers: put this one on your syllabi. The Suitcase, like much of Dovlatov's work, is an important part of the canon of Soviet-era literature, alongside Buglakov's The Master and Margarita and Lydia Chukovskaya's Sofia Petrovna.

No comments:

Post a Comment