Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game

by Michael Lewis. W.W. Norton and Co. 286 pages.

vs.

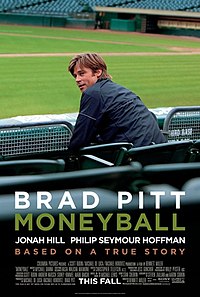

directed by Michael Bennett. Columbia Pictures. 133 min.

Comparing a book to its filmed version is a dangerous pastime: cinema and print are two different mediums and require different storytelling skills. One is visual, the other cerebral. Those that realize this invariably make good films - they steal the book's plot and maybe some of the dialogue, but otherwise they're wise enough to leave the book on the shelf. Moneyball is one such film. Written by Steven Zallian and Aaron Sorkin, Moneyball the movie is a taut character drama of a man against the world. Michael Lewis' book, on the other hand, is a far more complex expose of baseball's underworld and the personas behind both the players and those who put them on the film. Book and film are two different entities that have sprung from the same tree: the closest analogy one could give is that they are a pair of successful fraternal twins.

Lewis' book, written in 2003, has been such an influence on the world of baseball that apparently it's title has entered the baseball lexicon. An exploration of the Oakland Athletics' 2002 season - when they won 20 games in a row, among other miracles - Moneyball focuses its narrative on Oakland GM Billy Beane and his assistant Paul DePodesta as they form their team based on sabermetrics, a philosophy cooked up by statistician Bill James. Exactly what sabermetrics is isn't important, at least not for the purposes of enjoying the book (or the film). What matters is that it is a philosophy that flies in the face of conventional baseball insiders: in other words, Beane and co. were implementing a revolutionary system that threatened the status quo.

This threat is seen most clearly in the film, which structures the story around Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) and follows him as he squares off against angry scouts, a doubting media and an irrascible coach (an under-used Phillip Seymor Hoffman). Watching the film, one gets the idea that Billy and his assistant (played in the film by Jonah Hill) practically invented sabermetrics; Lewis' book, on the other hand, does a much better job providing the history of the idea which began as early as 1978.

Both book and film successfully convey the emotional benefit of sabermetrics: it tends to favor the underdog. And everyone loves an underdog, which is what makes it so easy to become involved in the characters. This isn't easy given that the crux of the conflict is the esoteric interpretation of baseball statistics: and all the authors, whether it's Lewis in his narrative or Zallian and Sorin in their screenplay, deserve to be applauded for managing to boil the narrative down to its more human elements.

For my money (pun intended), the film is slightly more accessible then the book. Lewis has written a fun expose, but his writing style is loose and occasionally unfocused. If the main character of the movie is Billy Beane, the main character of the book is an idea. By focusing the story on Billy and ramping up the urgency (there's a sense that 2002 was a do-or-die season for Billy Beane), the film manages to pull us along even though it's largely plotless.

Where the book does succeed is in delivering the lives of the underdogs who sabermetric theory saved from being put down. The movie hints at these characters but it's a Brad Pitt vehicle and they can only go so far. Lewis has a lot more latitude. Most affecting is the story of Scott Hatteberg, the Baptist catcher who is forced to play first base and ends up securing the Oakland A's 20th straight victory. In a fictional world, one would see the victory coming right from Chapter One; but in the world of non-fiction, it comes as a spectacular moment of truth colliding with dramatic necessity. The underdog triumphs or, to use the book's central metaphor, David faces Goliath and knocks one out of the park.

Still, it's hard to recommend Moneyball, book or film, to the baseball hater in your family. At the end of the day, Moneyball is still about baseball, with a climax crafted right out of the drama of the game. If you have no interest in baseball, you may find yourself coming down with a slight case of disinterest. On the other hand, the book / film may just rekindle your love of the game. I played baseball as a kid but, much to my father's shame, I was never very good (as you might guess, I was more interested in books). I haven't thought about baseball very much over the years, but Moneyball did a good job reminding me how much I adored my time on the field. Perhaps this is why I couldn't help but fall for Moneyball. Like so many of the players in the story, I was also an underdog. And it's nice to think that, based on sabermetric theory, even I might have been good enough to play in the majors.

I'm neither a fan of baseball or statistics, but Michael Lewis has the ability to explain both of them in such a compelling way, I couldn't put it down. I read it after watching the movie, and found a much more nuanced chronicle in the book. Well worth the read, especially if you enjoyed the movie.

ReplyDelete