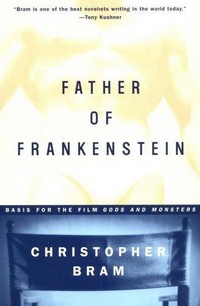

Father of Frankenstein

by Christopher Baum. Plume, 276 pages. Like author Peter Straub, I read most of this book in one sitting, a true compliment considering how restless one can get on a hot summer day. Reading this book so soon after Doctorow's Homer and Langley, I couldn't help but draw parallels, not because of the subject matter, but because both books create fictional versions of history that are true to the spirit of people involved if not the actual facts. Here, Mr. Baum's focus is the final days of James Whale, best remembered as the director of Frankenstien, who drowned himself in his Hollywood swimming pool in 1957. History is unapologetically subverted as Mr. Baum creates a tryptych of characters that are both wildly comical and deeply profound: Whale himself, his loyal maid Maria and Clayton Boone, an aimless yardman who shares Whale's final days.

Whale is notorious for being an openly gay director during a time when most homosexuals still lived in the closet, but for my money this is the least interesting thing about the book.But from a stylistic standpoint, Father of Frankenstien is also a perfect example of one of the great principles of storytelling: content dictates form. I'm borrowing Stephen Sondheim's phrase here, but primarily it means that the structure of a story is determined by the subject matter. Here, Mr. Baum captrues this principle chiefly through two important narrative techniques. First the novel is written in present tense, the same tense used in screenplays and film scenarios; and indeed, much of the book reads like a film scenario (not surprisingly, the book was turned into Gods and Monsters). The second technique is Mr. Baum's sudden chronological shifts from the present to various points in the past, thus echoing James Whale's own state of mind, rendered unstable by a stroke. For Whale, time had become fluid and Mr. Baum expertly captures this notion, sliding us from 1957 to 1932 or beyond in the blink of an eye.

Mr. Baum also avoids the usual pitfalls of bio-books, fictional or otherwise. He ignores the David Copperfield details (that's Sarah Vowell's expression - obviously today I'm incapable of coming up with anything on my own). Must of Whale's Hollywood life is left undiscussed, as is his longstanding affair with MGM producer David Lewis. Although Golden Age Hollywood makes an appearance, it never once steals the scene. No: the focus of the book remains always on Whale, Maria and Clayton Boone and in depicting these relationships, we learn more about Whale then we ever could from simple biographical details.

For the theatre fans, there is also an intriguing parallel between Father of Frankenstien and Edward Albee's first play, The Zoo Story (which was written in 1958, a year of Whale's death). Both stories focus on the relationship between two strangers, one of whom wants the other to kill him - in Mr. Baum's version of history, Whale wants Clayton to murder him and only kills himself after this fails; in The Zoo Story, the engimatic Jerry challenges Peter one day in the park. In both cases, the men use dishonor as the chief way to provoke the desired attack. In The Zoo Story, Jerry has challenged Peter's right to enjoy a particular park bench. When Peter objects, Jerry attacks:

Jerry: "....Tell me, Peter, is this bench, this iron and this wood, is this your honor? Is this the

thing in the world you'd fight for? Can you think of anything more absurd?

Peter: Absurd? Look I'm not going to talk to you about honor, or even try to explain it to you.

Besides it isn't a question of honor; but even if it where, you wouldn't understand.

(Signet Edition, pg 46)

And then later, after Peter kills Jerry:

Jerry: "...you've lost your bench, but you've defended your honor."

(Ibid. pg 49)

In the case of Father of Frankenstien, Whale uses the same tactic. After humiliating Boone by making a pass at him, he taunts him:

"You're not man enough to kill me? Not man enough to feel dishonored by what I did to you?"

(pg 246)

But in this case, the taunts don't work and Whale is forced to do what Albee's Jerry can't. What's interesting about this is the way both authors create similar characters - men who want to die - and have them employ similar techniques. It's a remarkable insight into male psychology that bears constant repetition, especially since it continues into the present day - look no further then the recent attack on a British Columbia student by her husband several weeks ago.

But whether or not you care about stylistic devices or parallels to famous one-act plays, Father of Frankenstien remains a novel that succeeds merely by being a damn good book filled with high comedy, shrewd insights and a surprising amount of suspense. This is first rate storytelling, with a narrative that is propelled forward by its own urgency and the compelling trio who make up the novel's cast. Read it on a hot summer's day at your own peril - and make sure to bring a hat.

No comments:

Post a Comment